Though Julian Assange is one of the most discussed individuals of the last decade, journalists and academics rarely make direct reference to his own statements—especially in the United States. Most of the time, those who comment on WikiLeaks feel entitled to impute ideas and behaviors to Assange, rhetorically transforming him from who he is into what they want him to be. After all, who is going to stop them?

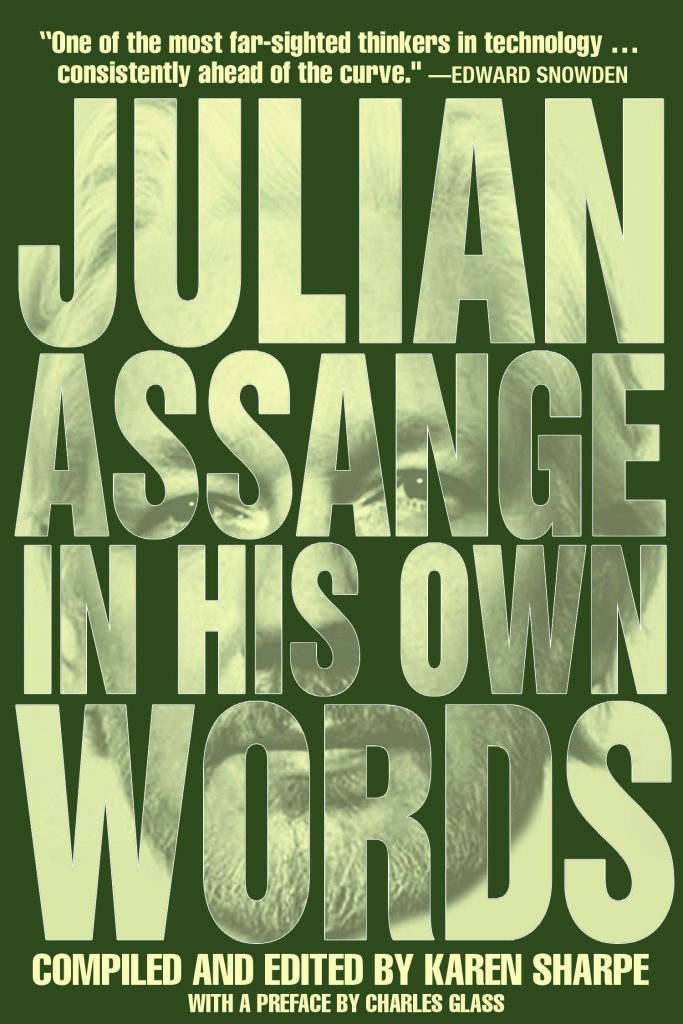

There was never a good excuse for not engaging Assange’s words directly, but now that OR Books has published Julian Assange in His Own Words, there is no excuse. Edited by Karen Sharpe and prefaced by Charles Glass, the book presents readers with approximately 140 pages of quotes from WikiLeaks’ founder. “Through revealing his his philosophy, politics, perspicacity, and humanism,” writes Sharpe in the semi-biographical introduction, “the quotations underscore the critical importance of this man who has done more than anyone to uncover how governments, politicians, corporations, the military, and the press truly operate.”

Assange’s philosophical views are scattered across hundreds of interviews, dozens of opinion essays, and several books. Sharpe collects statements most representative of Assange’s perspective and thematically organizes them into thirteen chapters: accountability, activism, censorship, empire, internet, journalism, justice, power, prison, society, surveillance, war, and WikiLeaks. Each chapter begins with an epigraph that establishes the theme. Every quote is both titled in a manner that highlights the main idea of the statement and accompanied by a footnote so readers can locate the original source and further explore Assange’s musings. Yet Sharpe would have been wise to follow Assange in using the archive.today resource so readers have access to stable links. Much of the source material included in the book was published between 2006 and 2016, which makes sense given the increasingly draconian efforts to silence Assange in recent years.

Some chapters, such as the chapters on censorship and journalism, are quite compelling and well constructed, while other chapters, such as those on accountability and prison, are not as powerful. Sharpe’s most important editorial decision was to include chapters on imperialism and war, two of Assange’s central political concerns. WikiLeaks cannot be understood without understanding Assange’s opposition to empire and war, and the quotes presented in these chapters decisively demonstrate this.

Sharpe sometimes takes Assange’s statements from substantive interviews he has given to journalists. There are hundreds of interviews to choose from, but Sharpe has drawn from about fifteen, three of which are heavily cited. There are at least nine quotes from the 2012 Democracy Now! event at The Frontline Club (with philosopher Slavoj Žižek), at least twelve quotes from the 2011 PBS-Frontline documentary WikiSecrets (video and transcript), and at least twenty quotes from Hans Ulrich Obrist’s interview with Assange, which was published in two parts by e-flux Journal in 2011.

When Sharpe is not quoting from interviews, she quotes directly from texts Assange authored, including his old blog, official statements to the press, and books like Cypherpunks, When Google Met WikiLeaks, and The WikiLeaks Files. Those who have read these books may discover insightful passages they previously overlooked, and those who have not read these books will receive a sampling of Assange’s broad intellectual interests. Most helpful are the quotes from Assange’s official statements, for such documents tend to be ephemeral and thus get lost to history.

Curiously, however, Assange’s opinion essays are entirely neglected. For example, key statements from his 2013 essay “How cryptography is a key weapon in the fight against empire states,” published in the Guardian, should have been included in the chapter on empire. Likewise, statements from his 2014 essay “Who Should Own the Internet?,” published by the New York Times, should have been included in the chapters on the internet, power, and surveillance. And his landmark essay “Don’t shoot messenger for revealing uncomfortable truths,” published in The Australian in 2010, is essentially required reading when it comes to Assange’s views on journalism and WikiLeaks. It is not clear why quotes from these essays would be excluded from the book.

The book’s intended audience is not defined by values but by knowledge. In other words, the primary audience for the book is neither Assange supporters nor Assange detractors but any person, regardless of their stance on WikiLeaks, who have never had the chance to read Assange’s own writings. To be sure, this group includes many WikiLeaks detractors, for they often condemn Assange without having studied anything about WikiLeaks outside the boundaries of corporate media propaganda. “This book serves as corrective to the disinformation surrounding Julian Assange and WikiLeaks,” writes Glass. “So many lies have circulated that the public has not had the chance to know what Assange has actually done and said.”

But this group also includes many WikiLeaks supporters, for not everyone who supports WikiLeaks has taken the time to understand the principles and ideals that inform the digital publishing organization. While I would not argue that one cannot be a “true” WikiLeaks supporter until they had read Assange’s entire corpus of writings, Assange himself suggests that his supporters must understand the ideas so they can carry them on when he is unable.

As the United States and United Kingdom continue to collaborate in their attempts to destroy Assange’s mind, this purpose becomes more urgent than ever. Medical experts have concluded that Assange displays signs of psychological torture, but anyone paying attention could see that his mental health and cognitive clarity is suffering. Compare Assange in this 2015 interview on Going Underground with his performance at the 2017 Holberg Debate and you will see what I mean. That was four years ago now. Assange won’t be able to act on his ideas forever. Others will have to pick up the torch.

Notwithstanding the book’s primary audience, those who have read a great deal of Assange’s writings or listened to hours of his speeches and interviews can still expect to learn a few things. As an academic who publishes research on WikiLeaks and editor of the WikiLeaks Bibliography, I thought I had read almost everything Assange as written or said in an interview. Yet I was delighted to discover interviews cited by Sharpe in which Assange explains that he cares more about justice and humanism than national security—a truly cosmopolitan perspective. Ultimately, Sharpe’s work will help me expand the bibliography.

Julian Assange in His Own Words stands as an important contribution to the public’s understanding of WikiLeaks, and Sharpe should be commended for her work. If it succeeds in its intended purpose, the book will serve as a gateway into the philosophical outlook of Julian Assange. Unlike dogmatic manifestoes, Julian Assange in His Own Words is a dynamic text and a conversation piece, which will hopefully stimulate deep reflection, meaningful dialogue, and fruitful debate.

But this book is only an important first step in the study of Assange and WikiLeaks. It is only a first step in the process of getting more people to get it right on WikiLeaks and getting more people to act on the principles that inform the organization. What we need next is an anthology of Assange’s writings, a book in which his most important essays and interviews are presented in full. Like my work at WikiLeaks Bibliography, Sharpe’s collection of quotes brings together disparate resources and provides readers with the means to further investigate Assange’s philosophical views.

If we are to truly acknowledge Assange’s status as a twenty-first century philosopher, if we are truly to respect his intellectual contributions, we seriously need a comprehensive book that can be studied in libraries and used in the world. As Assange wrote in his Letter from Belmarsh Prison, “the days when I could read and speak and organize to defend myself, my ideals, and my people are over until I am free! Everyone else must take my place.”