In January 2021, a United Kingdom court rejected the United States’ request to have Julian Assange extradited across the Atlantic. The judge stated that, while the US charges against Assange were legitimate, she feared that the harsh conditions of the US prison system would drive Assange to suicide. This decision was based on mounting evidence that over ten years of confinement has destroyed Assange’s psychological health. He has suffered a stroke. He has attempted suicide. And multiple international bodies have found Assange to be a victim of human rights abuses and psychological torture.

In December 2021, a higher UK court reversed the lower court’s decision on the grounds that the US government “assured” the court that Assange would be properly cared for in US custody. Given that the US power elite seem to hate Assange more than they hated Osama bin Laden, such assurances are quite laughable. For over ten years, in both recorded public remarks and in leaked information from closed meetings, politicians, spies, and pundits have called for Assange to be kidnapped, assassinated, and silenced. In 2010, Assange was a “high-tech terrorist.” In 2017, he was the head of a “hostile non-state intelligence agency.”

There is no question: this hateful treatment of Assange is killing him.

And yet—the lies continue, and among the worst culprits is the New York Times. In recent weeks, the Times has reported on developments in the Assange extradition trial and the paper’s editorial board has joined the conversation on the global state of press freedom. In both cases, the Times outright deceives its readership, making demonstrably false claims, or at least highly misleading statements, about the Wikileaks founder.

On December 10, the Times published “U.K. Court Rules Julian Assange Can Be Extradited to U.S.” by Megan Specia and Charlie Savage. The first few paragraphs consist of straightforward reporting on the hearings, but about halfway into the reporting, the authors sneak in the propaganda. As they write, “Mr. Assange fled to the Ecuadorean Embassy in London in 2012 when he was facing an investigation on accusations of sexual assault in Sweden, which was eventually dropped. He said he feared his human rights would be violated if he were extradited in that case.”

This remark is a modified version of the standard refrain “But he ran away from Swedish rape charges by hiding in Ecuador’s embassy in London.” As Jonathan Cook has detailed, Assange faced no charges, ever, for these accusations, and his principle reason for seeking asylum was that he feared that Sweden would be able to extradite him to the United States more easily than the United Kingdom. Assange explained in a December 2010 interview with Al Jazeera that his legal team advised him to remain in the U.K. where he would be safer from extradition. Had the authors said that Assange fled to the Ecuadorean Embassy because he was facing charges in Sweden, they would have lied twice.

But the authors are more careful, saying that Assange sought asylum “when” he was facing an “investigation.” These modifications to the refrain make the statement true, but it also leaves out the important point, namely, that Assange feared being extradited to the US where top officials had publicly expressed a desire to see him jailed or killed. Using the word “when” makes the comment trivial. If Assange was wearing a blue shirt when he sought asylum, then the statement “Mr. Assange fled to the Ecuadorean Embassy in London in 2012 when he was wearing a blue shirt, which was eventually removed and washed” would have the same truth value as what the Times wrote about Assange. The only difference is that “blue shirt” and “sexual assault” have very different connotations, and most Times readers are not going to unpack the subtle difference between what Specia and Savage wrote and the refrain “But he ran away from Swedish rape charges by hiding in Ecuador’s embassy in London.”

Furthermore, Specia and Savage state that Assange “feared his human rights would be violated if he were extradited in that case.” Why? They do not tell us and that is the whole point. What specifically was at stake for Assange? Extradition to the United States. The Times fails to provide the entire context for the statement, which allows them to say something trivially true while remaining within the confines of anti-Assange propaganda.

A second propagandistic claim in the reports comes when Specia and Savage discuss two sets of charges leveled against Assange. “The first is that Mr. Assange participated in a criminal hacking conspiracy, both by offering to help Ms. Manning mask her tracks on a secure computer network and by engaging in a broader effort to encourage hackers to obtain secret material and send it to WikiLeaks. The other is that his solicitation and publication of information the government deemed secret violated the Espionage Act.”

Having summaries the charges against Assange, the authors attack: “Hacking is not a journalistic act. But the second set of charges could establish a precedent that journalistic-style activities like seeking and publishing information the government considers classified may be treated as a crime in the United States—a separate question from whether Mr. Assange himself is considered a journalist.”

Hacking is not a journalistic act. The terms “to hack,” “hacking,” and “hacker” are never defined in reporting of this kind. These terms are ideographs. Michael McGee explains that ideographs are slogans, which are “easily mistaken for the technical terminology of political philosophy” and which are significant “in their concrete history as usages, not in their alleged idea-content.” Ideographs are expected “to do work in explaining, justifying, or guiding policy in specific situations.” McGee adds that ideographs are “one-term sums of an orientation…that will be used to symbolize a line of argument the meanest sort of individual would pursue…as a defense of a personal stake in and commitment to the society.”

Thus, an ideograph—such as “freedom of speech” or “the rule of law” or “hacker”—replaces argumentation while representing argumentation, allowing the writer or speaker to shorthand their way to a conclusion—so long as their audience understands the “obvious” conclusions that follow from the present-yet-absent argument.

The US government has accused Assange not of “hacking” but of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion. The government and their media stenographers call this “hacking,” but they do so because the term carries a negative connotation that does the work for them. Whereas “conspiracy to commit computer intrusion” suggests that evidence is required to determine whether some neutral—and perhaps presumably innocent—party is guilty of the offense, the term “hacker” suggests that the person is bad and therefore should be presumed guilty.

Huey P. Newton observes that “power is the ability to define phenomena and make it act in a desired manner.” The US government and the New York Times use their power to define reality and make it act in the manner they desire. In this care, they are defining Assange as a “hacker” hoping it will lead to his ultimate incarceration in the United States. Specia, Savage, and the editor at the Times are smart enough to use clear, accurate language, and they choose not to because they seek to define reality at Assange’s expense.

What could have been decent reporting was transformed into propaganda through the inclusion of half-truths and deceptive rhetorical obfuscations.

On December 18, just a week after Specia and Savage’s article, the Times editorial board published “A Record Number of Journalists Jailed,” its commentary on the Committee to Protect Journalists’ annual report for 2021.

“It’s been an especially bleak year for defenders of press freedom,” the CPJ’s 2021 report begins. The organization “found that the number of reporters jailed for their work hit a new global record of 293, up from a revised total of 280 in 2020. At least 24 journalists were killed because of their coverage so far this year; 18 others died in circumstances too murky to determine whether they were specific targets.”

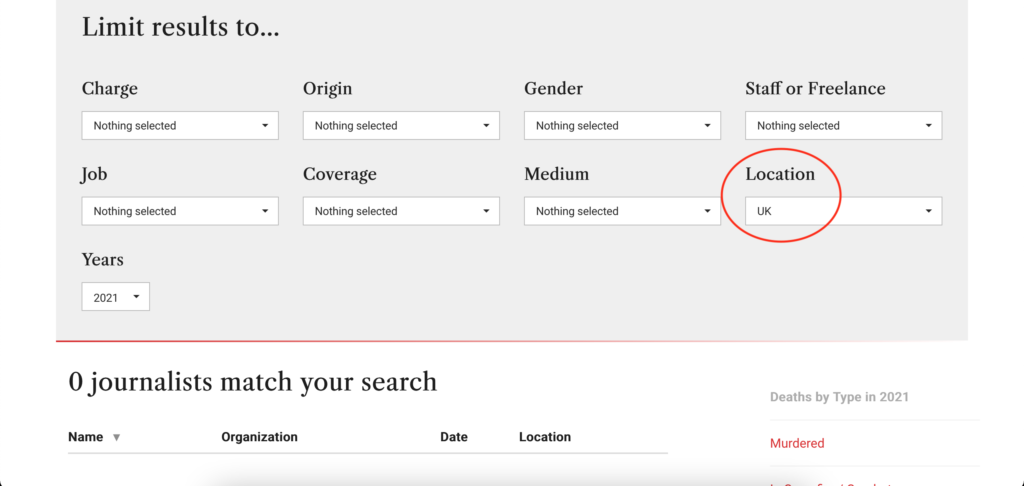

Puzzlingly, Assange is not included among the 293 imprisoned reporters. His name appears nowhere in list. CPJ doesn’t mention his name anywhere in their comments.

Returning to the importance of definitions, the report states: “CPJ defines journalists as people who cover the news or comment on public affairs in any media, including print, photographs, radio, television, and online. In its annual prison census, CPJ includes only those journalists who it has confirmed have been imprisoned in relation to their work.”

Assange covers news and comments on public affairs in print, on television, and online, and he is imprisoned for his work. Even Specia and Savage acknowledge this fact. Referring to “the Justice Department’s decision to charge Mr. Assange under the Espionage Act in connection with obtaining and publishing secret government documents,” they note that “the case against Mr. Assange centers on his 2010 publication of diplomatic and military files leaked by Chelsea Manning, a former Army intelligence analyst.” Assange’s case perfectly fits the CPJ’s definitional criteria, yet he is excluded from the report.

In its commentary on the CPJ report, the Times editorial board rums through the predictable list of “bad guy” governments—China, Egypt, Vietnam, Belarus, Turkey, Saudi Arabia—and complains of “authoritarian” states suppressing freedom of the press. “Authoritarian leaders,” the board writes, “seek to control and manipulate what is said and written with the sole purpose of remaining in power and above the law. They know full well that this violates freedoms enshrined in law and convention, which is why they so often attack journalists obliquely, using trumped-up charges like tax evasion and terrorism or drawing on vague and arcane laws to arrest reporters and shut down their operations.”

Certainly the government of the Times’ home country would never seek to control and manipulate what is said and written with the sole purpose of remaining in power and above the law. Certainly the US government would never attack journalists obliquely, using trumped-up charges like hacking or non-state espionage or drawing on vague and arcane laws like the Espionage Act and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act to arrest reporters and shut down their operations. Certainly not.

Unlike the CPJ, the Times editorial board discusses Assange in the context of repression of journalists. “The Committee to Protect Journalists report, however, coincided with the ruling of a British court that Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, can be extradited to the United States to face charges under the Espionage Act.” However, then mention Assange only so they can take the opportunity to lie about him and WikiLeaks.

Let’s unpack what the board says.

First, the board levels a self-serving criticism against the Biden administration for pursuing a case that threatens press freedom generally. “It is most unfortunate that the U.S. government has chosen to continue to use a law as potent as the Espionage Act to pursue Mr. Assange. There is a debate about whether Mr. Assange is a journalist, but equating the publication of classified materials received from government sources with espionage strikes at the very foundations of a free press and should be rejected by Mr. Biden.”

Second, the board seeks to maintain the apparent distinction (again defining reality according to their wishes) between “authoritarian” states who unabashedly attack journalists and “democratic” states, like the United States, who seek only to apply and enforce laws enacted by the legislature. “The drawn-out effort by the United States to try Mr. Assange in an open court where he could contest the charges under the First Amendment’s protection of press freedoms,” they write, “is qualitatively different from the incarceration of journalists by authoritarian leaders who seek nothing more than unchallenged power.”

This claim is patently false and utterly stupid—and the Times editorial board knows this. When prosecuted under the Espionage Act, the accused are not permitted to defend themselves in “open court.” They are prohibited from making public interest arguments as part of their defense strategy. How this differs from authoritarian leaders who seek nothing more than unchallenged power is a mystery. By prohibiting effective arguments in one’s defense, the US government literally designs a trial situation in which it has unchallenged power.

Third, the board falls back on yet another propagandistic refrain, namely, that WikiLeaks’ practice of publishing un-redacted (in WikiLeaks’ own language, uncensored) documents puts innocent people at risk of harm. WikiLeaks “released numerous documents leaked by an Army private without removing the names of confidential sources, putting lives in danger,” they claim.

Again, this claim is patently false and utterly stupid. And again, the Times editorial board knows this. As I have documented elsewhere, there is no controversy regarding the fact that WikiLeaks’ publications have never been linked to the harm of innocents.

The origin of this myth of harm to innocents goes back to July 28, 2010, when U.S. Navy Admiral Mike Mullen and Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates claimed that WikiLeaks personnel “might already have on their hands the blood of some young soldier or that of an Afghan family.” When a journalist asked, “Do you know, have people been killed over this information?,” referring to the Afghanistan War Logs, Mullen and Gates pontificated about the possibility of risk and the inability of journalists to understand military documents. The journalist retorted: “With all due respect, you didn’t answer the question.”

Yet the U.S. government admits that not a single of instance physical harm could be traced back to even WikiLeaks’ most provocative publications. As if Mullen and Gates’ evasive deflections were not evidence enough, on August 16, 2010, Gates himself admitted that his earlier accusation was completely false: “the review to date has not revealed any sensitive intelligence sources and methods compromised by this disclosure.” In 2013, when Brigadier general Robert Carr (the senior counter-intelligence officer who headed the Information Review Task Force that investigated the impact of WikiLeaks disclosures on behalf of the Defense Department) was asked in court to substantiate the claim that the Manning leaks had caused harm to innocents, Carr stated, “I don’t have a specific example.”

None.

Meanwhile, the Times is complicit in starting the Iraq War, which killed at least one million Iraqis. It is difficult to get one’s head around the obfuscations perpetuated by such nonsense.

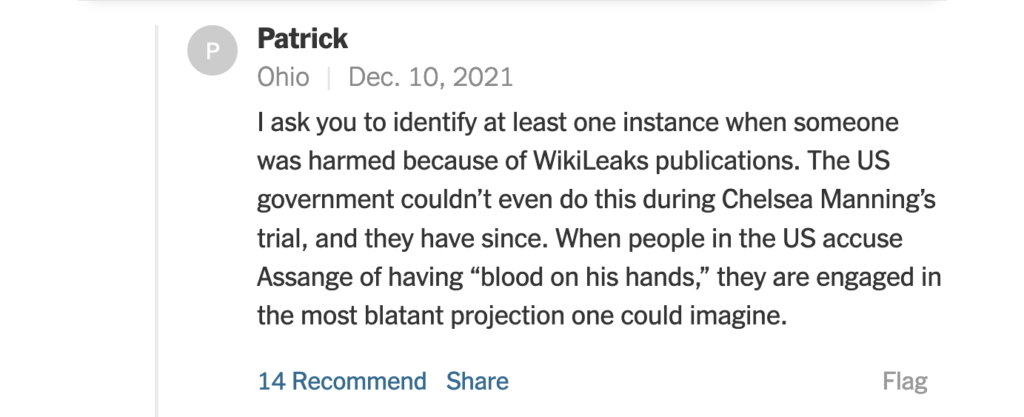

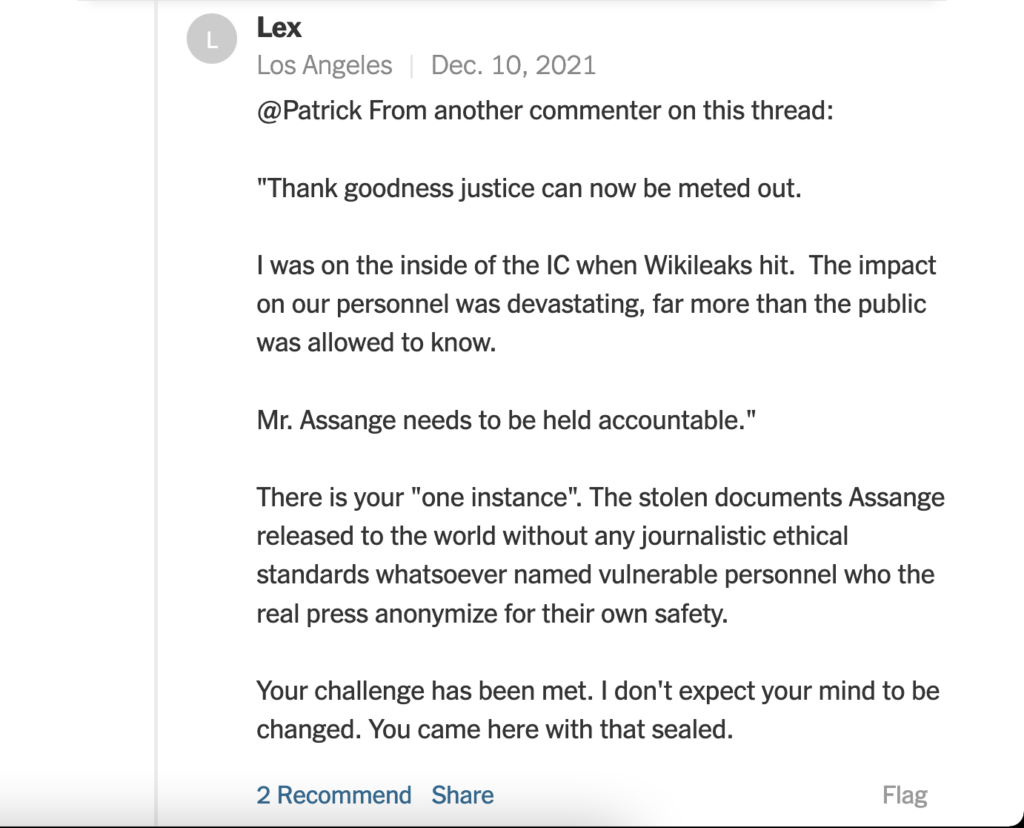

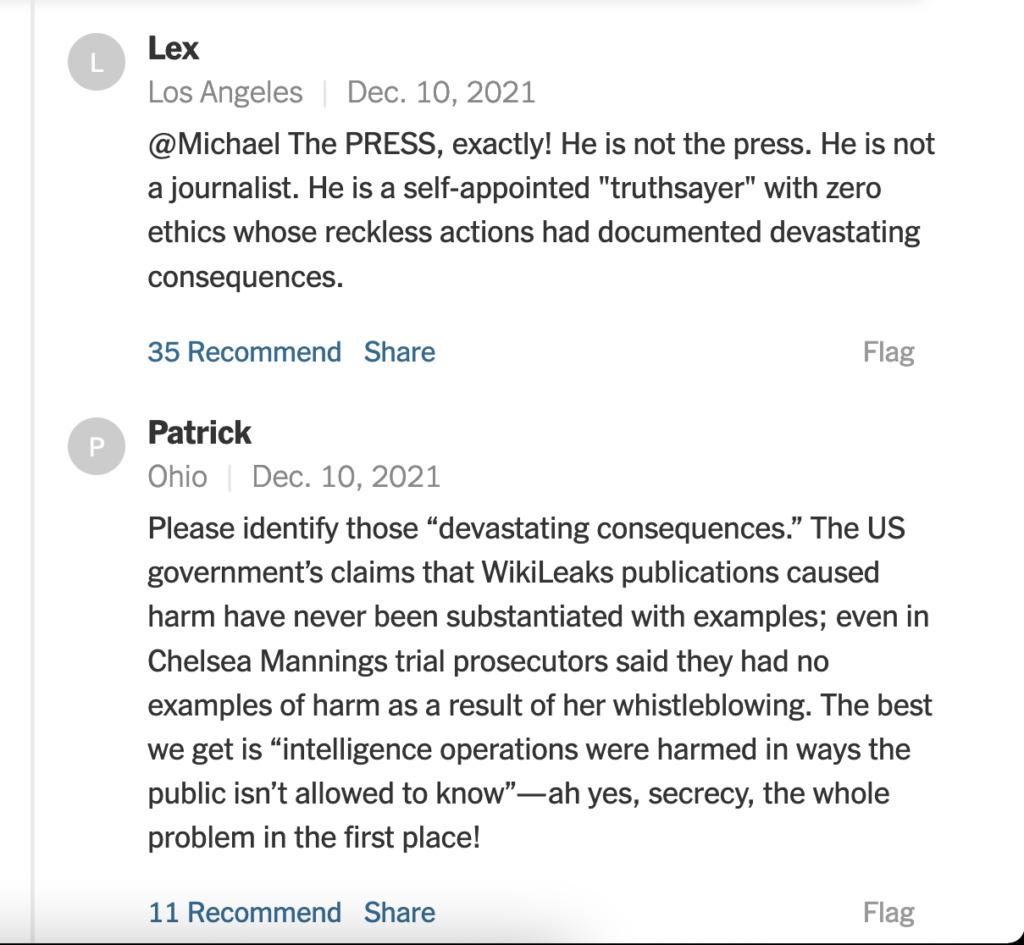

The biggest problem of all is that this kind of propaganda is very effective. When the Specia and Savage piece was published, I engaged the comments section for the article. There was more support for Assange than I expected of the New York Times readership, but many comments consisted of overwhelmingly false statements. I did my best to reply to falsehoods, and I was surprised that many (but not all) of my comments, which are often blocked by the paper’s moderators, were approved. Here, I present a sampling of the debates to illustrate the effectiveness of more than a decade of anti-WikiLeaks propaganda.

WikiLeaks caused harm to innocents

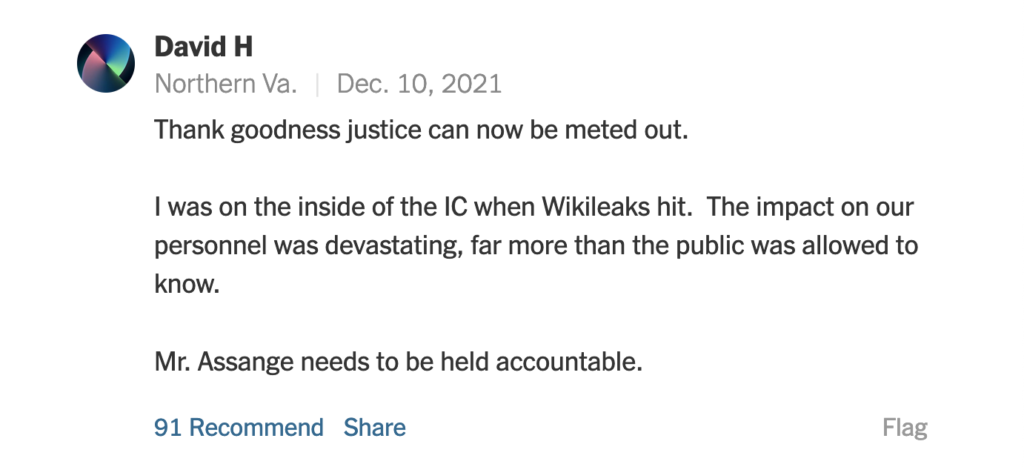

In that comment, Lex refers to this post by David H:

Thus, there are important questions to ask here. “The impact”…which was what? “On our personnel”…why should we presume their innocence? And why should we place them in the same category as civilians who were supposedly affected by WikiLeaks’ publications? “Far more than the public was allowed to know”…this comment makes the point for me. Secrecy was the problem, and now secrecy is being used to defend secrecy. Plus, we don’t even know that David H is telling the truth about being “on the inside of the IC” (intelligence community). People who complain about WikiLeaks not “verifying” sources sure have no problem marshaling comments from randos as definitive evidence of secretive claims.

I actually alluded to David H’s comment elsewhere:

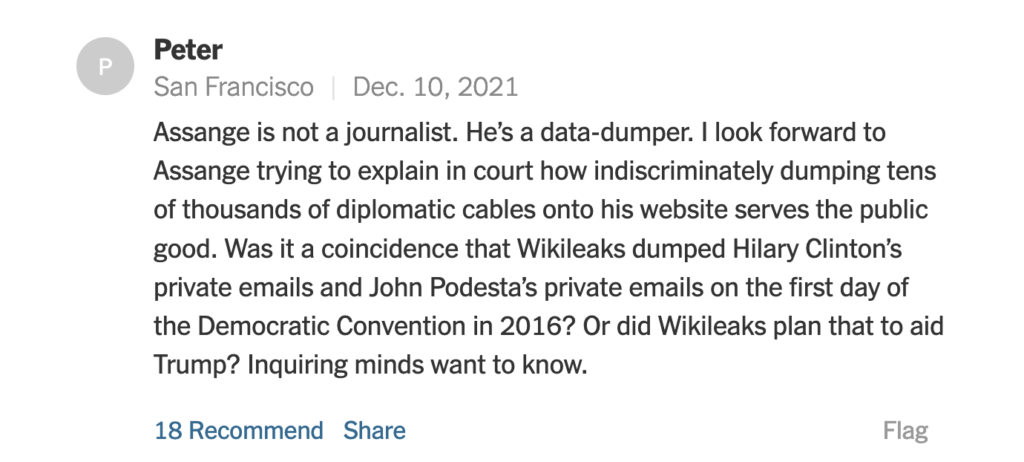

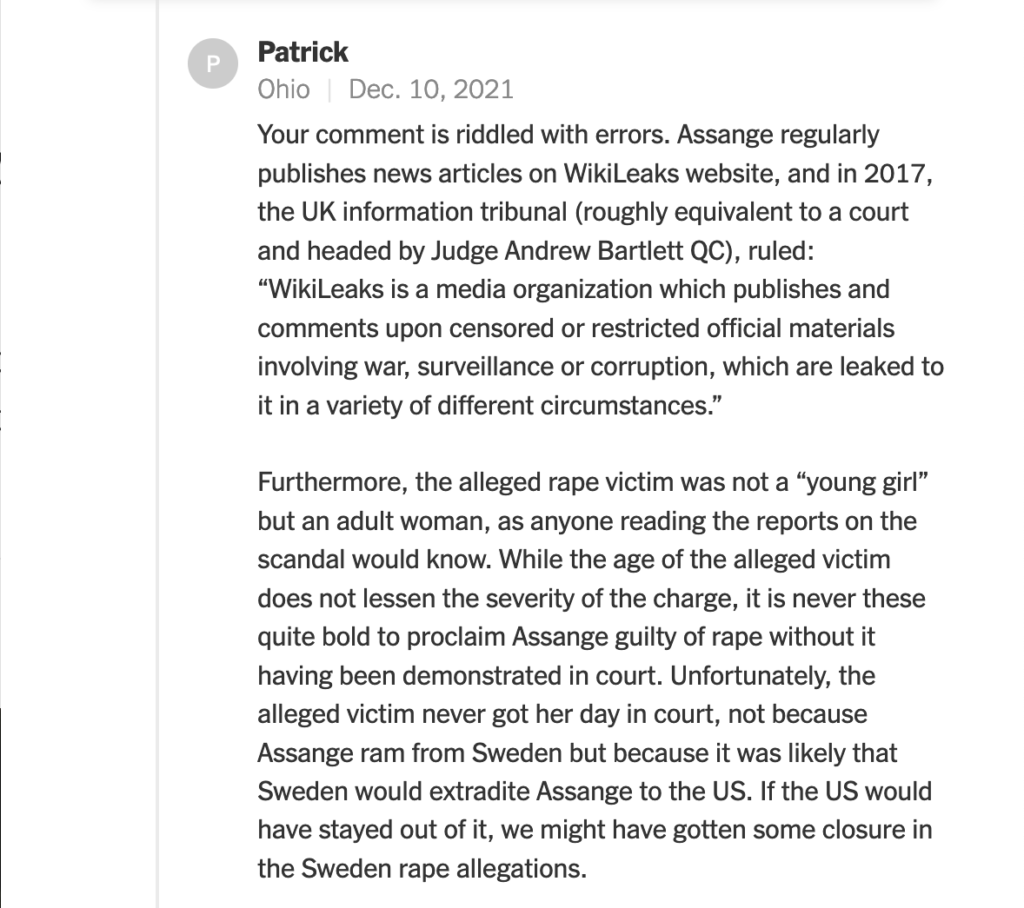

Assange is not a journalist

Assange will have his day in court

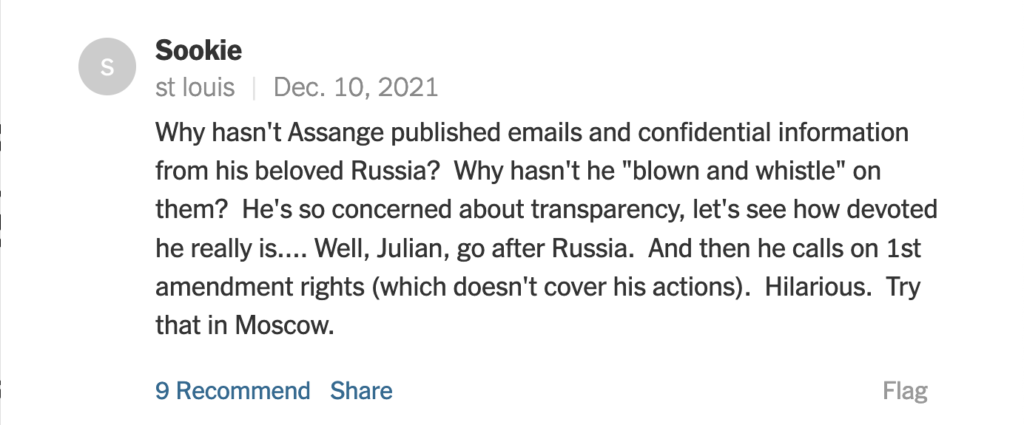

Russiagate Nonsense

And my favorite: Assange is a “traitor”

“Newspaper fire orange” by NS Newsflash is licensed under CC BY 2.0